Held in Osaka from March 15th to September 13th, the 1970 World Exposition was, along with the Tokyo Olympics of 1964, one of the events that most reflected the changes happening in Japanese society, and especially in the world of art, between the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s. According to scholar Yoshimoto Midori, Expo ‘70, as it is commonly known, has become in this century “one of the most frequently discussed topics in the Japanese art world”, and the subject and the setting of many comic books, movies, and books. It is worth mentioning here at least Urasawa Naoki’s manga 20th Century Boys (1999-2006), and Crayon Shin-chan: Storm-invoking Passion! The Adult Empire Strikes Back (2001) directed by Hara Keiichi.

Many of the people invited to participate in the event were part of a wave of artists that was affected by and shaped the 1960s, when art was conceived and practiced as a form of political activism and social resistance, a period kicked off in 1960 with the ANPO protests. The act of participating in Expo ‘70 was considered in itself, by many, a betrayal of what was theorized in the previous decade: a “selling out” to power and a symbolic gesture that (re)institutionalized art, after the urban and rural revolts of the sixties had sought a path outside of the official circles. However, for some of the criticized artists, the event “provided unprecedented opportunities to realize ambitious and big-budget projects that would otherwise never have been conceived” (Yoshimoto), and pushed artistic boundaries, helping to explore unkown creative landscapes.

One of the artists who joined Expo ‘70 was filmmaker and theorist Matsumoto Toshio. In the second half of the 1960s, with some of his short films, Matsumoto had reflected on the protests against ANPO, and more broadly on the artistic and political fervor of the time. For Expo ‘70, Matsumoto created Space Projection Ako, a work projected on ten screens inside a pavilion dedicated to textiles production. On the occasion of the previous World Exposition, held in Montreal in 1967, many artists had already begun to experiment with multi-projections films, for instance Canada ’67 by Walt Disney Production, a work in which the audience was surrounded on 360 degrees by nine large screens, where images of Canada were displayed. On the one hand, art funded by large companies, Space Projection Ako by a textile company, Canada ’67 by a telephone company. On the other, an experimentation that explored the limits, possibilities, and role of visual media, and intermedia, in contemporary society, thus casting a fascinating glance into the evolution of the relationship between technology and humanity.

It is in this socio-historical context that Teshigahara Hiroshi and Abe Kōbō collaborated once again—together they had already made at least three masterpieces: Woman in the Dunes, The Face of Another, and The Man Without a Map— to make what would become their last join effort, 240 Hours in One Day (1日240時間). A short visual experiment directed by Teshigahara and based on an idea by Abe, 240 Hours in One Day was sponsored and screened at the Automobile Pavilion during Expo ‘70. Rediscovered and restored only in recent years, the short film was shown on a couple of occasions in the past decade, and last March at the Osaka Asian Film Festival, a screening event I was lucky to attend.

…but they say that the passage of time that the dream fish experiences is quite different from when it is awake. The speed is remarkably slower, and one has the feeling that a few terrestrial seconds are drawn out to several days or several weeks.

The Box Man, Abe Kōbō

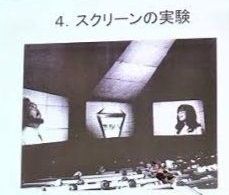

The short film was originally projected at the World Exposition on four screens, three arranged horizontally, the fourth, trapezoidal in shape, placed almost on the ceiling. At the Osaka Film Festival, the work was projected on one flat screen with the 4 original screens forming an upside down T, so to speak (the still that opens this article gives hopefully an idea of it).

240 Hours in One Day is set in a city of the near future, where Dr. X and his female assistant have successfully developed a miraculous drug. When inhaled, this medicine, an accelerator known as Acceletin, allows the user to function ten times faster than normal, perhaps a reference and homage to the protagonist of Alfred Bester’s novel The Stars My Destination (1956), or Ishinomori Shōtarō’s Cyborg 009. At first, people celebrate the newfound freedoms offered to them by this miraculous drug that extends a single day to 240 hours, but gradually things start to change.

Teshigahara experiments with a dizzying combination of genres, and the tone is always playful and joyous, a bit all over the place to be honest, and probably by design, because the work does not take itself too seriously. In this regard, it reminded me of the best and most delirious PR movies (industrial films) of the 1960s, such as Noda Shinkichi’s Nitiray A La Carte (ニチレ・ア・ラ・カルト) (1963) or Kuroki Kazuo’s 恋の羊が海いっぱい (1961).

Science fiction, comedy, musical, animation, documentary, and metafiction are weaved together in an aesthetic divertissement that is also a light critic of the obsession of our society with speed and production. The film also offers an obvious reference to the changes produced by the invention of means of transportation; after all, the film was screened in the Automobile Pavilion. What particularly stood out to me is the inventiveness of the different cinematic styles used, and how the four screens are used to create a cinematic viewing experience that is spatially different from the usual one: the characters move freely from one screen to the other, and sometimes each screen represents a distinctive point of view on the same scene.

As pointed out by Tomoda Yoshiyuki, professor and scholar that did a short but fascinating talk after the screening, in the last scenes of the film, when the doctor runs away and spins so rapidly that he becomes a wheel of light and colours, Teshigahara and Abe are hinting at something different that goes beyond the pure negative sides of an accelerated society. The two artists are pointing towards the post-human changes and becomings that new technologies inevitably bring with them, a becoming-thing that was one of the themes often touched by Abe in his books.

Reference:

– Expo ’70 and Japanese Art: Dissonant Voices An Introduction and Commentary, Yoshimoto Midori, Review of Japanese Culture and Society, Vol. 23, 2011.

– The Box Man, Abe Kōbō, Vintage, 2001.